What do you think of when you hear the term “biophilic design?”

While green walls, daylight, or a view of nature likely come to mind, these are only a sliver of the many attributes that make up this concept. Biophilic design is derived from the term biophilia, which describes humans’ innate connection and affinity towards the natural world. Coined by biologist E.O. Wilson in 1984, the term reflects a response to humans’ blatant disconnect from the natural world parallelling rapid technological advancement.

Biophilic design integrates strategies based on beneficial affiliations between humans and the natural world into our built environment. It stems from the positive physiological and psychological effects that nature can have on human psyche, which has been widely studied with overwhelming evidence in the field of biophilia.

A RICH HISTORY

In order to see the ways that biophilic design is more than a green wall, just glance at these research-based frameworks that have generated a pathway to implement biophilic design into buildings:

• The 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design

• Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life, which is the foundation of the Biophilic Environment imperative in the Living Building Challenge

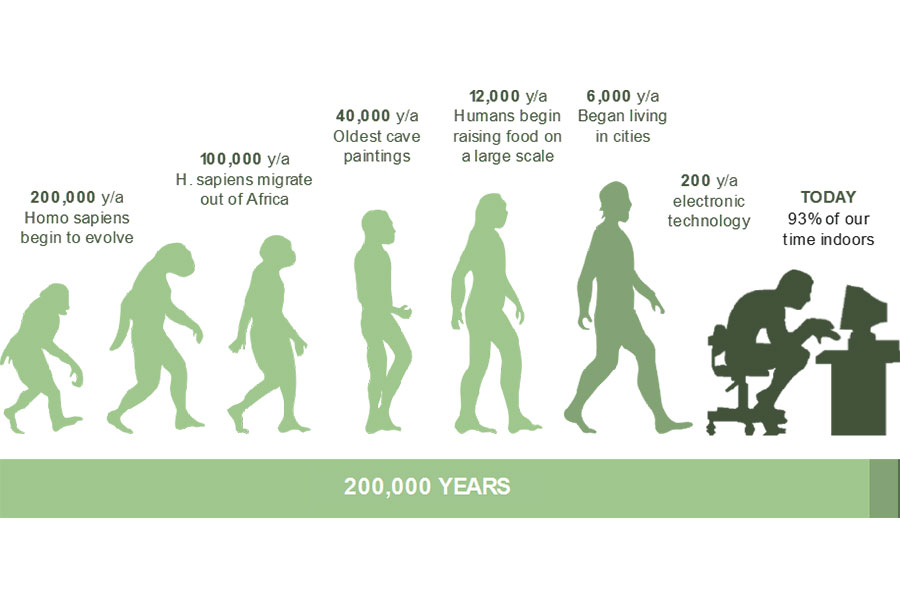

Looking through these frameworks, you may be asking, “where did this all come from?” The answer lies in humans’ evolutionary history over the last 200,000 years in the natural world. Dense constructed and engineered environments, dominated by hard surface, high-rise buildings, and technology have only been prevalent for less than 0.2% of the human timeline. Thus, from an evolutionary standpoint, separation from the natural world is un-natural.

Factors that enabled our ability to survive and thrive within nature during the 99.8% of our evolutionary history are numerous, including an intimate understanding of place, seeking shelter for protection, an ability to find food, and a propensity for exploration. These traits are locked into our genetic memory and explain the complex connections between humans and natural systems.

Effective biophilic design provides benefits and solutions that people and our planet are in desperate need of. First, it utilizes stimuli to elicit positive responses that combat a multitude of mental and physical stressors brought on by overwhelming technology and excessive exposure to non-natural environments. While different design strategies cause different specific responses (which can be used strategically in different building use types), improved health is always the aim. Next, good biophilic design uses both subtle and overt elements to remind us that we are a part of nature. In an increasingly urbanizing world, we need these reminders to be strong and to be everywhere in our non-natural environments. Implicit in biophilic design is the hope that it not only serves as a restorative force for humans experiencing it, but also reminds us of our instinctual connections to the natural world, stirring our sense of affection and responsibility towards it – and not a moment too soon.

There are many ways to reimagine our built environment to be rich and immersive in nature. The following are just a few strategies from the biophilic design frameworks that will widen your perception of biophilic design.

PLACE-BASED RELATIONSHIPS

At one time, architecture was necessarily based on place. By looking at a structure, one could tell what materials were found there, what the weather was like, and what was important to the people that lived there (think igloos, the Parthenon). Architecture gave insight into the essence of that place. This distinctiveness created a special relationship between people and the places they inhabited – a connection largely absent in our buildings today, which are increasingly homogenous across the planet.

Creating place-based relationships is essential to biophilic design. Doing so inherently promotes our human needs of a sense of familiarity, connectedness, and emotional attachment. Place-based design warrants a deep understanding of a place, discovered often through research and questioning. There are countless inspirations to draw from, including historical events, current culture, geography, ecology, or local materials – whatever helps communicate the distinctiveness about a place worth celebrating. Also required is an agreement among the design team on specific elements that will establish these place-based relationships. And yes, this can and should be done in today’s corporate offices.

Examples of place-based relationships include:

Te Kura Whare Tuhoe | Taneatua, New Zealand

Te Kura Whare was created with the intention of restoring pride in the Tuhoe culture and the people’s inherent connection to the land. Located at the entrance to the town of Taneatua and built of natural materials, sense of place is expressed through many of the building’s features. For example, the timber comes from dead and downed native trees within Tuhoe Rohe to reflect the Tuhoe’s strong relationship with the forest. Further, the arch symbolizes the rising sun, representing action and progress to this indigenous culture.

Google Chicago HQ | Chicago, IL

The Google Chicago Headquarters has unique art installations that celebrate Chicago’s history on every floor, from its transit system to famous parks. The office incorporates historical references through art installations and an industrial structure that fosters a distinct sense of place.

PROSPECT & REFUGE

Finding prospect and refuge is something that has allowed humans to survive as a species. While for many of us, our survival is no longer dependent on finding places of prospect and refuge, our innate need to observe (prospect) without being seen (refuge) is still ingrained in us.

Compare the photos below: a structure built in pre-A.D. 1200s and a modern-day structure. They both demonstrate the architectural aspect and landscape design of meeting humans’ need of prospect and refuge.

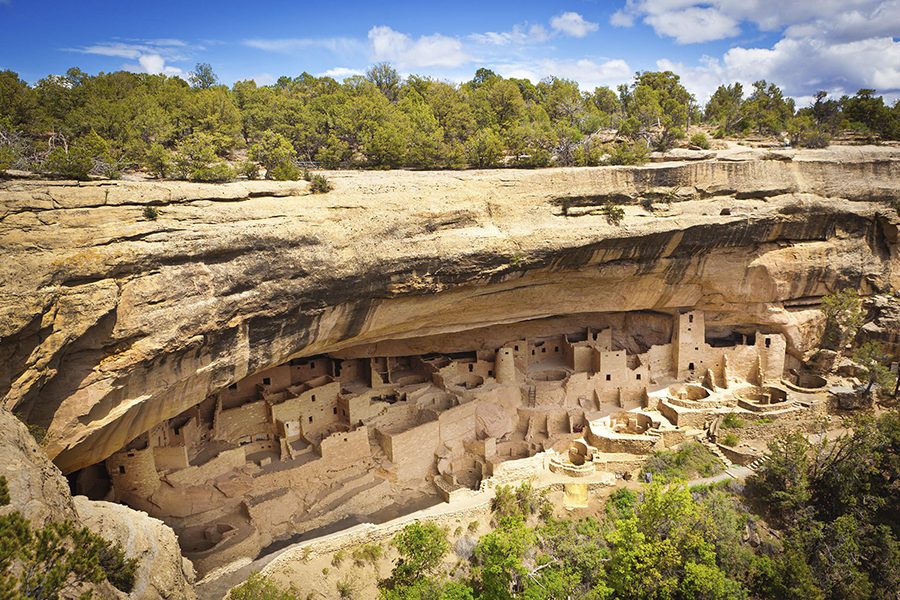

Cliff Palace | Mesa Verde, CO

While the Cliff Palace settlement provides a sense of shelter and protection from both the climate and potential predators or enemies, its position of elevation and views overlooking the canyon also satisfy the need for prospect.

Mosaic Centre for Conscious Community & Commerce | Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

As Alberta’s first net zero, LEED Platinum certified commercial building, The Mosaic Centre’s enclosed rooms portray the theory of prospect and refuge. The rooms cultivate the sense of shelter and protection through the use of large glass windows while providing an overlooking view of the project’s primary communal open space.

FEAR & AWE

Think about how you feel watching a 40-foot wave break in front of you, or our fright and fascination of heights, depths, and shadows. In the biophilic design frameworks, this is referred to as fear and awe. Incorporating design elements that foster them activates an enhanced physical and mental state of awareness.

Studies have revealed a biological connection between our experiences of fear and awe. Researchers have found that natural threats can actually elicit positive emotional reactions in humans. Responses to certain kinds of risk release strong, short doses of dopamine, which enhance analytical, motivational, and recall functions in humans. Incorporating elements that introduce controlled risk in the built environment creates opportunities for these healthy neurological pleasure responses.

Park Tower | San Francisco, CA

Park Tower features 14 sky decks. The outdoor areas resting on the highest floors of the building have transparent glass railings, giving individuals a sense of height looking down and a view of the San Francisco skyline, evoking both fear and awe in its design.

Fort Worth Water Garden | Fort Worth, TX

The Fort Worth Water Garden’s maze of elevated, unprotected pathways over levels of gushing water brings fear and awe to a dynamic community space. Visitors experience a rush as they hop along the raised stepping stones without railings or other means of stability and safety. At the same time, visitors can pause on a level terrace or sit by the sunken pool to take in their fascinating surroundings – a gaping, enticing urban water garden.

RESTORING OUR CONNECTION

While the built environment today demonstrates our extraordinary advancements as humans, much of it has come at the cost of unbridled environmental degradation; created unhealthy separation between humans and their natural environment; and has generated new, often inescapable stressors on our psyche. Biophilic design has tremendous potential to be used as a restorative force in addressing all of these.

We invite you to explore and play with these frameworks, which feature the most beneficial highlights from our 200K-year evolutionary journey. They offer exciting opportunity to incorporate elements into design that engender healing across several realms. You’ll see in your exploration how biophilic design is so, so much more than a green wall!

Keep on the lookout for more resources to help you meaningfully weave biophilic design into your projects. In the meantime, contact our team to learn more about biophilic design and how to apply it to your own work.